Lobo Creators Interview – DJ Arneson & Tony Tallarico

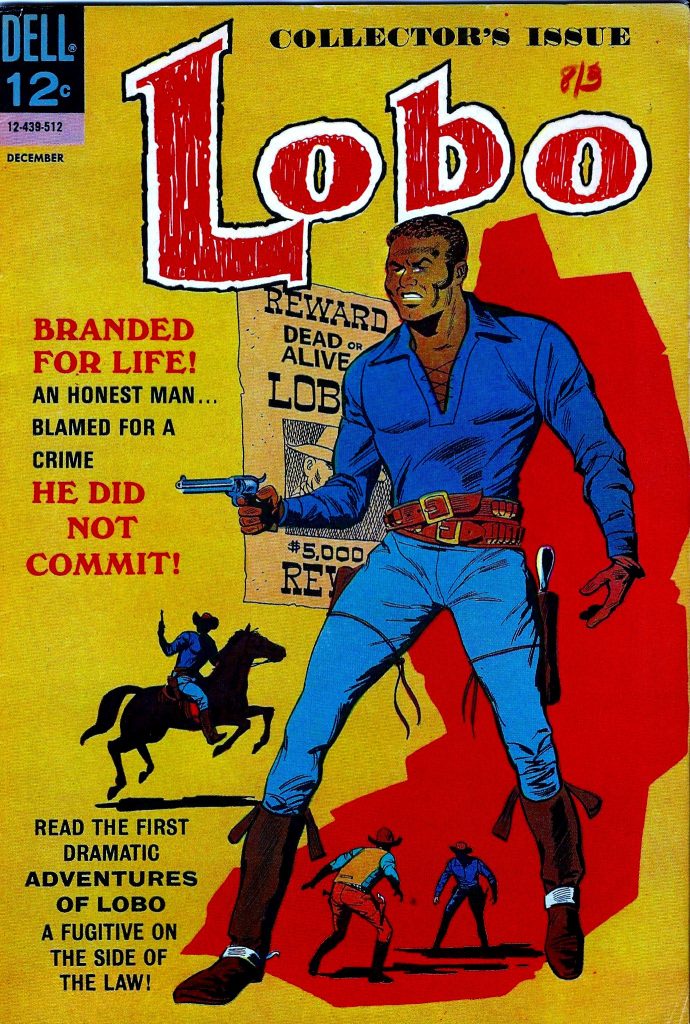

During my research into comic book history I learned about Lobo, the first black comic book character with their own solo title. This was published in 1965, long before Marvel’s Black Panther. There was little to no information about Lobo’s creators. It was known that Tony Tallarico drew the comic book.

During my research into comic book history I learned about Lobo, the first black comic book character with their own solo title. This was published in 1965, long before Marvel’s Black Panther. There was little to no information about Lobo’s creators. It was known that Tony Tallarico drew the comic book.

I had read online that Tony was to receive a Pioneer Award at the 2006 ECBACC Convention. I reached out to William Foster III regarding contacting Tony for an interview. He was only able to provide me with a mailing address, advising me Tony wasn’t able to appear at the convention and he had read an acceptance speech on his behalf. From the mailing address I was able to find his phone number.

I called on a Sunday and got voice mail. I left a message introducing myself, my desire to interview Tony and saying I would call back next Sunday. When I called back next Sunday Tony was there and was happy to do the interview. We spoke and I transcribed the interview. The interview call and it’s transcription is reprinted below. It was originally published in August 2006.

I figured that would be the end of it until March of 2010. My editor got an email from an upset DJ Arneson, who was the writer and editor of the Lobo comics and insisted he was also the creator of the character. He gave specific details on what inspired the character and felt Tony’s version of how the character was created were wrong. DJ also disputed many of Tony’s statements regarding Lobo’s cancellation too. My editor suggested I do an interview with him to get his side of the story, which I did. I e-mailed DJ, proposed an interview and he agreed, giving me his number. We did the interview and that was published in April of 2010.

With both interviews we talked more than just about Lobo. Tony a long career in comics and we discussed some of the editors he worked with and his work appearing in the notorious Seduction of the Innocent. We also talked about his work on The Great Society and Bobman & Teddy two political parody comic books that got mainstream media attention at the time. DJ Arneson was the last editor of Dell Comics, which was once the largest, most successful comic book company in North America. Besides Lobo, we talked about Helen Meyer, who was the President of Dell Comics and likely one of a very few female company Presidents in the United States at that time. We also discussed other creators at Dell, how licensing worked for comics and his work outside of Dell including his writing for Tower Comics & Archie.

Below is Tony Tallarico’s interview, then please make sure to read DJ Arneson’s as well.

—

Tony Tallarico worked in the comic industry from the 1950s to the 1970s. His work ended up in Seduction of the Innocent, he created the first solo character book devoted to a black hero, and he’s done a number of what Scott Shaw! calls Oddball Comics. In this phone interview we go through his comics career and what he’s been doing since.

You can either hear the interview here:

(30 minutes long, 28 megs – turn your volume up)

Or read the following transcript.

Jamie: What was your first work?

Tony Tallarico: Oh!

Jamie: Do you remember that?

Tony Tallarico: Yeah, Of course (laughter). I did some things for Charlton when Al Fago was the editor. They were for Hot Rod and Racing Cars. I did a bunch of cartoon cars, very similar to the Disney movie Cars. Only they were done a long time ago. Before that I was an assistant to a cartoonist. His name was Frank Carin who was an animator.

Jamie: Did you do any animated movies at all?

Tony Tallarico: No, and he wasn’t doing any animation either. When I knew him he was doing comic books. He was packaging these small sized comic books for Acme Supermarkets. There were 4 titles, I remember them distinctly. One was Doh-Doh the Clown. Another one was Captain Atom that Lou Ravielli did. His brother was a famous sports illustrator. Dave Gantz did and it was a teenage character. The 4th one was the first comic book and the first work really that Jack Davis did was called Lucky Stars. He had just come up from the south. I don’t know how he met Frank Carin but that was the very first comic book he did. Before he even worked for EC.

Jamie: Oh wow, I didn’t know that. You said Captain Atom. Was he like a superhero?

Tony Tallarico: Yes.

Jamie: Any similar relationship to the Captain Atom from Charlton that came later on?

Tony Tallarico: No. This was way before. It was probably.. I’m going to take a guess.. I was still going to high school.. probably 1950.

Jamie: You were working for Charlton. What was the company like then? How did it operate?

Tony Tallarico: Al Fago had an office on 42nd street and Broadway, right on Times Square. The building was just torn down a couple of years ago. It was very impersonal, you just go up, show him what you had. If he had a script for you you’d take it back. Otherwise you’d play the game of calling him up asking for work.

Jamie: I know later on Charlton was known for paying very low page rates and it was piecemeal. Was it like this?

Tony Tallarico: No it was a little better at this time. I mean, they weren’t paying anything great, but I think they were paying about $25 dollars a page.

Jamie: That was around 1950s?

Tony Tallarico: That was around 1950. Early 50s, 51 tops.

Jamie: I’m curious, I know L. B. Cole worked on some of the covers of the books that you did. Do you know him well?

Tony Tallarico: Well, I knew him. I don’t know if he’s still around.

Jamie: I’m not sure either.

Tony Tallarico: He was also the editor of Classic Comics for a while. He was also the editor of Dell when Dell pulled away from Western Publishing to start up their own comic book operation. He was the editor.

Jamie: What was he like?

Tony Tallarico: (sigh)… he treated me very nice.

Jamie: He treated you very nice.

Tony Tallarico: He always did. But a lot of people did not like him. And there was always talk that he was on the take. I can only say that he was always the one that took me to lunch. I never paid for a lunch. I never gave him a nickel and I never even heard of it. Lately I have heard stories like that. I can’t believe it.

Jamie: Moving up a little bit at Charlton you were working on Blue Beetle. And I know some of your work ended up in that notorious book Seduction of the Innocent.

Tony Tallarico: Yes it did (laughter). I was working for a Sol Cohen. He was the editor of Avon Comics. This must have been 1953-1954.

Jamie: That would be about right.

Tony Tallarico: At that point they were taking paperback covers that they had, they had the separations all done and transporting them into comic book covers. And the one that I worked on was… it was one of these whip and black stocking covers that they had. I edited down, cut it down so there was very little showing. But that’s one of the ones that made it into the book.

Jamie: (laughter) The one you toned down is the one that made it in the book.

Tony Tallarico: Right. Had I never toned it down it would have been on the cover! (laughter)

Jamie: That’s funny.

Tony Tallarico: They were notoriously cheap, Avon. And so was Sol Cohen. But they paid well and they had good people working for them. Woody was working for them at that time. Everett [Raymond] Kinstler was quite a number of good guys doing work there. A. C. Hollingsworth worked. Oh I know, Rex Maxon.. [also Wally Wood and Joe Orlando]. He did, I don’t know if it was his first comic strip but he did Daily Tarzan. He was really more like a pulp illustrator. He had that rough.. it did not translate well in comics. For some reason he was very friendly with Sol Cohen so he got lots of work. He did Kit Carson, that was the book that he did.

Jamie: I know you did a lot of work with Bill Fraccio? (wrong pronunciation)

Tony Tallarico: Fraccio. (correct pronunciation)

Jamie: How did you meet him?

Tony Tallarico: I met him at Frank Carin, Bill was doing some work for Frank. He was doing a thing called Sunny Sunshine. It was a little girl character for Sunshine Bakeries that they gave away every few months. Frank was the packager of the book and Bill worked for him. That’s how we met. We did a lot of things together.

Jamie: Yeah there is a lot of mix up if he was inking you or if he was penciling.

Tony Tallarico: It’s not a mix up because we were doing both. I would pencil some, he would ink some, visa versa y’know one of those things. I was really the guy that went out and got the work. Bill never liked to do that. It would depend. If he was working on something else I would start a project too and do pencils. It was a fun time.

Jamie: I want to move over to your Dell work. You did an important comic book called Lobo.

Tony Tallarico: Yes. Two and a half issues.

Jamie: Two and a half? What happened to the other half? I know two issues got published.

Tony Tallarico: Well I have some of the pages here. They never got published. Lobo.. well lets back up a little bit here. At this point L. B. Cole is no longer the editor at Dell. His assistant a guy named D. J. Arneson hey, nobody had first names, they had letters. D. J. Arneson was the editor. He had an idea for a book and he approached me with it. I did a sample cover which showed it to Dell. Dell turned it down, they didn’t want anything to do with it. We went over to a book publisher and he loved it. It was the Great Society Comic Book. It was the first Adult Political Satire. Nothing had been done for a while since Kennedy was assassinated. This was the first humorous look at politics some two years later. We did it and gee, it got on the New York Times best seller lists. It was featured in Newsweek magazine. It was in a hundred newspapers as a news story, not as a book. It was on radio, television, we sold foreign rights to it, did a real bang up job on it.

Just about that time I had an idea for Lobo. And I approached D. J. Arneson and he brought it in and showed it to Helen Meyer. Helen Meyer was the editor of all of Dell. She was the first female to become the president of a publishing company. A very important historical note, Helen Meyer. She loved it. She really wanted to do it. Great, so we did it. We did the first issue. And in comics, you start the 2nd issue as they’re printing the first one due to time limitations. We did the 2nd one and it was being separated while the first one was being distributed. All of the sudden they stopped the wagon. They stopped production on the issue. They discovered that as they were sending out bundles of comics out to the distributors and they were being returned unopened. And I couldn’t figure out why? So they sniffed around, scouted around and discovered they were opposed to Lobo. Who was the first black western hero. That was the end of the book. It sold nothing. They printed 200,000 that was the going print rate. They sold.. oh.. 10-15 thousand. It was tremendous because they never got on to the newsstand. So that was the end of Lobo. It’s kind of funny because after all these years Temple [University – School of Arts and Sciences] honored me for doing it. It never succeeded on the stands but it did break a little ground I hope.

[Note: They gave Tony a Pioneer Award – Lifetime Achievement in the Comics Industry on May 19, 2006]

Jamie: It did because afterwards you saw black heroes everywhere. Marvel put out Black Panther.

Tony Tallarico: Yeah but that was much later.

Jamie: That was much later, but Lobo was the first one.

Tony Tallarico: Yup, this was 1966. Marvel Comics.. they were late 70s or even early 80s. A great deal of time has passed and by then it was an accepted thing. It wasn’t a novelty. And it wasn’t meant to be a novelty. Lobo was a veteran of the Civil War who was accused wrongly of a crime who tried to.. y’know it was not goofy, it was a pretty straight thing. But it never got off the ground. Simply because the distributors were prejudiced bastards.

Jamie: Who wrote Lobo, the first issue?

Tony Tallarico: We wrote it together D. J. Arneson and I. It was my idea and I knew what I wanted to do and he just put it together.

Jamie: Okay that was the big question we all had. We knew that you drew it but we didn’t know who created the character and what was behind it.

Tony Tallarico: I created and D. J. and I, we wrote it together. It wasn’t really writing, it was interpreting the character, I guess we wrote it.

Jamie: Was he scripting it or more plotting it?

Tony Tallarico: I really plotted it. He scripted it.

Jamie: Okay, you did the plot and he did the script?

Tony Tallarico: mmm-hmm.

Jamie: Before you mentioned The Great Society and then you did Bobman and Teddy.

Tony Tallarico: That was the sequel to The Great Society.

Jamie: I was wondering, how did those sell the newsstand?

Tony Tallarico: They sold very well. I was on Walter Cronkite on the news. He did an interview with me. I couldn’t believe it (laughter) this is a comic book we’re talking about here. But like I said, we had no humor for like two years and this broke a comic relief. In fact, about two years ago I got a letter from the Johnston Library in Austin Texas. I don’t know how they tracked me down. They said they would like to have a copy of the book and anything else I may have to put into their library to put into their permanent collection. I looked around and I sent them a poster of the book that we used and a copy of the book.

Shortly after that I got a letter from Linda Bird Johnston asking “Do you have an extra one for me?” (laughter) I said sure and I sent her one, and she sent me an autographed picture of herself. Now this is funny, I have it hanging up on my studio with a lot of other stuff. About 6 months ago I discovered her signature faded. You can’t read it and it looks like an unsigned photo. In the throws of next week or so I’m going to send it back to her and say “hey, did tricky dicky do this? (laughter) and can ya re-sign it for me.”

Jamie: I know those books, they had covers that were made with anti-tear paper?

Tony Tallarico: Yeah, it was really a very lightweight board. Instead of a varnish on it, they had a varnish that looked like Kansas. It had a tooth to it. It really bulked up the cover. Because a lot of these were sold in bookstores, very few of them were sold on the newsstand.

Jamie: Wow. Did you sell very much on newsstands or was it..?

Tony Tallarico: No, no, it was like maybe the American News Company. The better newsstands, the ones in airports.. not the mom and pop stores. But we had very little returns and we sold a heck of a lot. We sold maybe 5-600,000 and this was a $1 comic book. This was an unheard of thing.

Jamie: Quite a bit more than 12 cents.

Tony Tallarico: Oh yeah, and it was not a kids book. It was an adult book.

Jamie: Was wondering why you didn’t continue doing more of them after Bobman and Teddy?

Tony Tallarico: Well because the fad ended. It was a quick fad. We were kind of lucky because Batman and Robin were on TV as a put on and that helped the sales of Bobman and Teddy. The Great Society sold 500,000 and Bobman and Teddy sold 150,000. The writing was on the wall, you’re not going to do another one.

Jamie: I know you went over to Warren and did a lot of work for them.

Tony Tallarico: Oh yeah, in fact Bill and I worked together. We had.. I can’t think of it.. we made up a name..

Jamie: Oh yeah, Williamsune.

Tony Tallarico: Williamsune! Tony Williamsune.

Jamie: I had heard Al Williamson he just left Warren at the time and he didn’t like the name because he thought people would confuse you with him so you had to change the spelling of the name a little bit.

Tony Tallarico: Right.

Jamie: I know you drew one of the earliest Vampirella stories in the first issue.

Tony Tallarico: That’s right. In fact I worked on the character sketches. I think they used some of them. But I definitely did stuff on the first issue of Vampirella. I got a Christmas card from him, I get a Christmas card from him every year.

Jamie: From Jim Warren?

Tony Tallarico: Yes.

Jamie: What is he up to these days do you know?

Tony Tallarico: Yeah he keeps saying he’s going to come back, he’s going to do this and do that but I don’t think he has the money to do it. At that time he was really in with the distributor. Which most comic publishers were. It’s a big nut to finance. By the time you get paid it’s 6-7 months. If you putting out a bi-monthly, you putting out a lot of money for art, printing, distribution and so on. It’s a big nut. I mean, a major publisher like Dell could do it, no problem. Even Timely or Marvel at that time they had their own distributor. Atlas was the name of the distributor but which was the same company.

Jamie: At Warren publishing, they everything in black and white just about. Did you like working in black and white vs. color?

Tony Tallarico: Yeah it was fun and it was different. With the exception of The Great Society, Bobman and Teddy and a couple of things I did for Classic Comics I never got the say on the color. It was given out to the coloring studios and whatever color they put in that was it. This was an opportunity to do black and white, just what you wanted that was it. So it was good.

Jamie: Did you do any work for Marvel or DC in your career?

Tony Tallarico: No. It’s funny because when I graduated from high school, I went to a high school that specialized in art. It was called the School of Industrial Arts. A lot of people in the business went there. Al Toth, who just passed away, Joe Giella, anyway, when I graduated I won the Superman-DC award which was a drawing table. And it’s the one I’m still using! That was my last touch with Superman. Our paths just never crossed. I was always doing something else and I just never went there. The same thing with Marvel. The closest connection to Marvel was.. oh Cracked? or Sick?

Jamie: Oh yeah one of those..

Tony Tallarico: Yeah, one of those things.

Jamie: Might have been Brand Ech or something like that.

Tony Tallarico: Yeah right. That was uh.. Layton? He was the editor. I really got out of the comic book area in the early 70s. Well the comic books left me. In the 70s the whole business went kaput. Luckily I was able to transfer over into doing children’s books. I’ve been doing children’s books ever since. My wife went though a count several months ago. It was over a thousand titles. That’s a lot of children’s books. One series that I did for Kids Books has sold like 16-17 million copies world wide.

Jamie: Yeah I heard about that one.

Tony Tallarico: That’s an enormous amount. And it’s still selling, they just dressed it up a little. Put on a new cover or whatever.

Jamie: Was there a particular character or genre that you liked to work in within the comic industry? Did you prefer cowboys or horror or was it all just work?

Tony Tallarico: It was a little of everything. I did whatever I could get a hold of it. Most people did. I don’t know any artist that really specialized in a particular thing. Can you think of one? Jack Davis was pinned into doing westerns until he went to EC. Then he started doing everything. The only think I don’t think he did was a romance story.

I did a romance cover one time for Charlton. You have to remember Charlton paid very low and because of that you had to do an awful amount of work. I did a splash page where a couple is embracing and the girl has 3 hands. I meant to whiten one of them out, but I never got to it (laughter). And it went all the way through! (laughter) it was kind of funny. The editor didn’t think so, but hell, it was his fault too, he looked at it.

Jamie: Yeah, he didn’t see it himself so..

Tony Tallarico: Right.

Jamie: Well lets go back a little bit and who were your inspirations for drawing was it like Caniff or..

Tony Tallarico: Oh sure. In my days it was Caniff, Raymond and Noel Sickles. Those were the three. For illustrators, of course [Norman] Rockwell and Al Parker and Austin Briggs those were it. Austin Briggs did comics, he did Flash Gordon for a long time, Al Park was more of a designing illustrator.

Jamie: Did you ever try to get into comic strips at all even as a ghost?

Tony Tallarico: Oh yeah. I and my wife did a strip for 17 years. It was called Trivia Treat. It was 3 panels on a page. One was an illustrated question. The next two were written questions. And there was an answer upside down. It was based on Trivia. It was based on whatever was popular, Hopalong Cassidey, whatever. The thing lasted 17 years.

Jamie: When about did it start?

Tony Tallarico: uh…

Jamie: do you know when it ended?

Tony Tallarico: It ended in the mid 90s. By that time my wife had withdrawn from it and my son was writing it. He also does a feature for Tribune Syndicate. Tribune was the Syndicate for this, Trivia Treats. My son does a thing called Word Salsa. It’s a word search puzzle that is half in Spanish and half in English. It’s been running for about 3 years and it’s in about 75 papers.

I also did a thing called Zap the Video Chap. Which lasted a year, that was for the McNaught Syndicate. And I ghosted some stuff. I did Nancy for a while, Davey Jones which was an adventure strip. I can’t think of any others.

Jamie: Did you do any cartoons or advertising?

Tony Tallarico: Oh yeah sure. I had a studio in the city, or space in the city with an ad agency. And I did lots of stuff. Ford, sing a song issue. Pan-Am was a very heavy user of comic books. For the GIs to take a Pan-Am flight back to the states when they got week or 10 day leave or whatever.

Jamie: Did you do any other work for the army or was it just through Pan-Am?

Tony Tallarico: No, it was strictly through Pan-Am.

Jamie: Did you serve any time at all, in the army?

Tony Tallarico: No.

Jamie: Managed to bypass all that eh?

Tony Tallarico: It was just one of those things. I was too young, then I was too old.

Jamie: I guess you’re one of the lucky ones (laughter).

Tony Tallarico: Yeah, right exactly. I didn’t plan it that way.

Jamie: I guess you’re parents did.

Tony Tallarico: I doubt it. Speaking of my parents, when I was 12-13 I told them I wanted to be an artist and they were really happy about it. As the word got out through the family they said they were nuts and I was wasting my time. Well, 50 some years later I don’t think I wasted my time.

Jamie: If you made a good living out of it then you definitely didn’t.

Tony Tallarico: Yeah and I enjoyed it, I still enjoy it and I’m still doing it.

Jamie: So what are you doing now and days?

Tony Tallarico: Kids Books are my primary account. I do just about everything that they & I come up with. Just stepping back a bit, I also create my own stuff, and sometimes my son writes it with me. Just about everything I come up with, Kids Books sponsors and publishes. Right now I’m doing a series of picture find books based on classic stories. The first one is based on Tom Sawyer. I think we’ll be doing about 10 or 12 and after that it will be famous people. Muhammad Ali is in there, Rosa Parks. It’s their life stories, but with hidden pictures in it. So the kids will be a part of the story.

DJ Arneson was the editor of Dell Comics between 1962 and 1973, the company stopped publishing comics after he left. He also did some freelance writing, both for titles he was publishing at Dell and for other publishers. Much of his comic book work is uncredited. DJ originally got in touch with us when he read the Tony Tallarico interview I had conducted in 2006 and disputed Tony’s version of events. This lead to doing an interview about his career in comics done mainly over the phone but with some questions by e-mail.

Jamie: There is very little information about you out there. When and where were you born?

DJ Arneson: I was born in Minnesota, small town out on the Midwestern plains. I was born in 1935 that makes me 74 years old as of right now. Moved to Boulder, Colorado, graduated from Boulder High School, went to the University of Colorado, then went to the army and worked for Counter Intelligence. I worked out of the American Consulate in Stuttgart, Germany for a couple of years. I moved to Mexico and completed my education, majored in Philosophy, minored in Psychology. I returned to this country, ended up in New York and for a period of time at Dell Publishing.

Jamie: Did you have any siblings?

DJ Arneson: I have two sisters. Both younger than myself.

Jamie: What did your parents do?

DJ Arneson: My father was killed when I was 5 years old. My mother was self employed and that pretty much covers that.

Jamie: What does DJ stand for?

DJ Arneson: Don Jon. D-o-n J-o-n.

Jamie: Did you have any interest in comics growing up?

DJ Arneson: Yes, as a little kid. I grew up basically during the 2nd World War. The war was over on my birthday in 1945. I remember that period rather well. I also remembered reading comics at the local pharmacy. They had displays and kids would sit there and read them for free until the proprietor would say “the library is closed.” Then we’d all scoot out and then come back the next day. It was very common reading at the time. I had a collection as probably every kid my age did, which would eventually been worth kajillions, I suppose. They ended up in somebody’s attic and ultimately I’m sure, in the trash sadly as tons and tons of comics were.

Jamie: So, you don’t have any of your old comics anymore?

DJ Arneson: No. As a matter of fact, tragically when I was younger, I was more interested in the new comics than the old ones. While I was at Dell I had a collection of everything Dell did while I was there, as well as all of the comics from other publishers. I had a room in the basement that was stacked with comics. My young son would bring his friends and they would revel in comic books. We moved to Europe in 1973. I bought a VW pop top camper and we traveled around Europe for a couple of years. Anyway, when we sold our home in Connecticut in 1973 all of those comics disappeared. My youngest son at the time, who was 7 lamented that. There was a treasure trove of comic books that simply disappeared. That was pretty much the history of any comic I collected at Dell.

Jamie: That is a shame.

DJ Arneson: It is. You read stuff in the New York Times, this comic is worth this much, or somebody is looking for a copy of Superman or whatever. At one point I had some of this stuff, but it’s all gone.

Jamie: What made you want to work in the comic book industry?

DJ Arneson: Well, as I said I went from Mexico to Denver, Colorado and came to New York. I answered an ad in the New York Times for an Editorial Assistant. I was interviewed for the job that turned out to be at Dell Publishing. I was interviewed by the editor at the time, his name was Leonard (Len) Cole. I was also interviewed by Helen Meyer who was the President and I was hired for the job of Assistant to the Editor. About one month later, this was April, 1962, Len Cole was.. lets say let go, without getting into the details there. My understanding is that he was “let go” but what the actual circumstances were, I do not know. Helen Meyer called me into her office and asked me if I was capable of doing this job. I said yes I am, and she said okay, you are now my comic book editor. So I didn’t come into comics with a long history of working in them. I came into the publishing industry and it turned out my entry was through Dell Comics. I was there until I moved to Europe. Prior to moving to Europe, I had gone to Helen Meyer and told her I wanted to go freelance and become a freelance writer. She said she couldn’t accept that, but offered me the opportunity where I could come continue as staff editor, come in for half a week and the balance of the week I would be for my own work. That was a deal I could not refuse, so I did that for 2-3 years. Ultimately I went full time freelance.

Jamie: Did you do any writing for comic books?

DJ Arneson: Yeah, I wrote comics while I was at Dell under a couple of conditions, one was as editor – there were times when a writer would deliver material that was frankly unacceptable. In which case I wrote the script for the comic that was due. We were always under deadline pressure. When the work was due to go to the artists, there wasn’t any flex time in that. So on a few very limited occasions I re-wrote the script, going by the original storyline that was submitted to me by the writer, which was the practice of the time. I’ll go into a little detail about that. When Dell chose to publish a comic, I would select a writer and that writer would do a brief storyline out of which I would determine if it was a good story, and then the writer would do a synopsis for me, which I would then approve for a script for the comic book. By the time that came in the deadline pressure had begun and it had to go very, very quickly to the artist. On a limited number of occasions the script was simply unacceptable I had to rewrite it. Once I had established that I was doing freelance writing, and I cleared that with Helen Meyer and she was very cognitive that I was writing comics for Dell. From that I segued into going full time freelance.

Jamie: Did you work for other publishers doing freelance writing?

DJ Arneson: Sure. I did work for Charlton, Gold Key, I very briefly did stuff for Archie. That was maybe 2 or 3 stories in 1 or 2 issues.

Jamie: Do you remember what issues or series?

DJ Arneson: Well, I did Dark Shadows the first 2 issues. I created the comic book from the TV series. It was a popular Television series. Wally Green, who was an editor of Gold Key had the license to do the comic book. I did the first 2 for sure and I might have done more after that. Also I did, when I was little they called them big little books, they were little fat books, but I did one of those for Dark Shadows. [Note: This was Dark Shadows Story Digest Magazine #1]. I did a bunch of stuff for Charlton.

Jamie: For Archie I assume they were just random stories?

DJ Arneson: They were done anonymously and I’m reluctant to even mention doing them. I recall they required storyboards that had to be sketched. At the time I was not a credible sketcher. I only did a couple of stories and like I said, I’m almost reluctant to even mention them. I do recall they required storyboards and that just didn’t come naturally, I’m a better writer.

Jamie: So you only wrote, didn’t do any artwork at all?

DJ Arneson: No, no. I wouldn’t presume to be an artist then. Whatever I do now is strictly amateur stuff. But no, I did not illustrate.

Jamie: Did you know George Delacourt?

DJ Arneson: Sure.

Jamie: What was he like?

DJ Arneson: George Delacourt was the President of Dell. He was involved in an extremely limited way. He wasn’t in his office at all. Helen Meyer ran the company and did it very, very well. My interaction with George Delacourt was extremely limited. Yes we met, I was in his office on 3 or 4 occasions. We never did lunch or anything like that (laugh). He was kind of an old guy at the time and left the management and running of the company to Helen Meyer.

Jamie: My next question was about Helen Meyer, what was she like?

DJ Arneson: She was very business driven and very personable if you were able to reach her. Let me put it this way. She was a very proficient business woman. When you dealt with her, it was strictly all business. But she had a very warm side, I’d say as I dealt with her on a steady basis. We would take a cab to go to a screening of a movie or a TV series, projected to be opening in the following fall. We would have conversations in the cab that were comfortable. I was 26 years old at the time and she would say you’re more like my son than my editor. At the time it was nice to be considered that way. My point is she was very personable to me. But she was very difficult with some, because she was all business. She knew what she wanted and her decisions were virtually always good. She was the boss. So there was normal reaction of somebody, an editor of a book or magazine, that you had to go through the boss. And it would depend on the circumstances of the meeting. But my recollection and memory of her is very, very warm.

Jamie: Where you the only editor at Dell at the time?

DJ Arneson: We had an art department for the production of the covers. There was no stable of artists or staff artists. There was art director for the comic book covers. I reported directly to Helen Meyers, that is to say the editorial material that I requested from writers, the synopsis and manuscripts. Ultimately the manuscripts would end up in Helen Meyers’ office. I’m not suggesting that she read all of them. If I had a suggestion, a comic book idea or whatever, she would be the last word.

Jamie: When the comic were written at Dell, how were they done? Was it full script or “Marvel” style?

DJ Arneson: At Dell it was all written directly from scripts. That is the writer… and I didn’t really have any women writers at the time. That’s really a bad commentary isn’t it? But there just were none. They were very similar to a screenplay. Also while I was at Dell, I read tons of screenplays as we considered them possible comic book clients. Point is, at Dell comics the manuscripts or storyboard, and I don’t mean art storyboard, but screenplays with description of the art, everything broken down in panels, the art and the dialog all created at the same time. The level of art direction in the panels would vary. In some instances the writer would say ‘backyard’ or whatever, a simple description of what was called for. In others, I would say they over directed because that was part of the fun in my mind is coming up with the images and writing them out. The short answer is they were not done in the Marvel style.

Jamie: You came in just as Dell and Western Printing split. Do you know what that was all about?

DJ Arneson: My recollection is when I joined, Dell Comics was Dell Comics, plain and simple. Len Cole was the editor and I do not know for how long he had been the editor. I frankly don’t know the circumstances of what the split was about. That was between Len Cole and Dell. I don’t know what the break up was other than what I subsequently learned the financial and ownership considerations. Dell broke with Western, Dell Comics maintained the Dell Comics logo. Dell created a new line of comics and a lot of what was published was an attempt of getting a hold of the glory days of comic book publishing that Dell had during the late 40s and 50s.

Jamie: It was in 1962 that Four Color Comics stopped and a bunch of 1 shots or 2 issue runs were published that would have normally been in Four Color. Do you know anything about that?

DJ Arneson: No. I don’t know anything about that. Which one shots are you referring to? We did do a lot of one shots. Often times with television clients, they would run for a period of time and it would be more than a 1 shot. As far as movie clients, they were 1 shots because once the movie came out, that was the end of that.

Jamie: Dell got the licenses for TV series and even some musical acts like the Monkee’s…

DJ Arneson: I wrote the Monkees.

Jamie: Oh you did! I understand the artist was Jose Delbo?

DJ Arneson: Jose Delbo, he was really a terrific person, a wonderful illustrator. I don’t know anything about him now. The last I dealt with him was on a political satire comic called First Cowboy Comix. It made fun of Ronald Regan and Delbo illustrated it and that was the last contact I had with him. That was in the 1980s. But yes, Jose did the illustrations for the Monkees and I wrote it.

Jamie: Was there a lot of having to go back to the licensor and getting it all approved with the Monkees?

DJ Arneson: No, there was no approval. We had the license to do it and there was no approval by the licensor. We did the comic and I don’t recall ever a licensor getting back to us. It all would have been after the fact as the book would have already been published.

Jamie: Was all the licensors like that?

DJ Arneson: While I was there I don’t recall any licensed product that required approval by the licensor.

Jamie: Going back to the Monkees for a bit, I know there was a paperback of Monkees comics put out by Public Library, were you also involved in that?

DJ Arneson: No, I don’t know anything about it.

Jamie: What was John Stanley like?

DJ Arneson: I did not know John all that well. He was an established writer long before I met him. He had a close relationship with Helen Meyer, Dell’s president.

Jamie: What was Don Segall like?

DJ Arneson: Don was a reliable writer whom I counted on when a new title was acquired to deliver a manuscript quickly.

Jamie: I know you disagree with what Tony said about the creation of Lobo. What is your version of the events of how Lobo was created?

DJ Arneson: Tony Tallarico illustrated Lobo. He did not create the character, I did. He did not plot the storyline, I did. He did not write the script, I did. And he did not approach me with the original concept or idea. The concept, development and writing that became Lobo were mine.

It’s totally out of character for me to bother commenting on this kind of off-the-wall petty issue but in this case I’m compelled to do so because, frankly, it staggers me to believe that Tony said what this interview indicates he said. I cannot fathom why he would do so. It is an egregiously self-serving statement which, in addition, is personally demeaning to me by baldly stating, among other flatly false claims that: “It was my idea and I knew what I wanted to do and he (D.J. Arneson) just put it together.”

My responsibilities as editor included researching and developing material for new comic books as well as hiring the writers, illustrators and others required to produce Dell Comics. Tony was among the illustrators I hired; I never hired or assigned or used him to write anything.

I developed the original premise for Lobo (originally Black Lobo, a title Helen Meyer rejected as inappropriate at the time–this was the mid-60s when civil rights and other social issues were volatile) from the book The Negro Cowboys by Philip Durham and Everett L. Jones; Dodd, Mead, 1965. The book sits in front of me on my desk.

On reading the book in 1965, I recognized the potential for a black comic book hero based on historical fact; the Buffalo Soldiers, the name given to African-American Union soldiers in the American Civil War. A number of those soldiers went west and became cowboys following the war and I conceived Black Lobo as a dramatic characterization of this little-known history. Again, this was 1965, a time when African-Americans were still referred to as Negroes, for example. Sit-ins, segregation and social upheaval were still entrenched in the United States. Martin Luther King was still very much in the future as a national figure and symbol of the revolution underway. The idea of a black comic book character, much less the title character in his own comic, was unusual to say the least. That Helen Meyer, a trail-blazer in her own right as the only female president of a major publishing company, and incidentally, the highest paid female executive in the country at the time, made the decision to publish Lobo is a tribute to her intelligence, foresight and sensitivity.

I added other elements to the original Black Lobo character concept, e.g.: Robin Hood, The Lone Ranger etc. as well as the familiar adventurous spirit of the American cowboy of popular western novels and cowboy movies of that time to dramatize and expand the character and storyline to portray a black comic book hero; there were none at the time. The intention was to create a series, but that didn’t happen as comic book historians and enthusiasts now know. Bummer.

Tony illustrated a mock-up cover, titled Black Lobo, which was presented to Helen Meyer along with the proposal I wrote based on what I described above. Helen Meyer agreed to publish the proposed comic book as Lobo.

I then wrote the script and Tony Illustrated the comic book from my script for which we were each paid Dell’s going rates for writers and illustrators (embarrassing low, but that was a lifetime ago); that is, the rights to the character and the comic book were not bought by Dell but automatically became copyrighted Dell property as was the usual procedure for commissioned work. An entirely different process is followed for the contractual acquisition of original material. I mention this to underscore the fact that Lobo was not offered to Dell as a property created, owned or copyrighted by anyone outside the company.

I have no idea on what information or source, proprietary to Dell or other, Tony based his explanation for the discontinuation of Lobo. Sales were the primary basis for the continuation or discontinuation of a series title. I neither have now nor did I have at that time any intimation or suggestion that Lobo was discontinued because anyone was somehow conspiratorially “opposed” to it. On the other hand, I know very well, as I’ve briefly stated above, where Lobo began.

Jamie: I know you did a couple of political comics with Tony Tallarico, the Great Society and Bobman and Teddy. Can you tell us how those came about?

DJ Arneson: The first one was The Great Society comic book. Let’s me jump back a little bit, there was 2 guys at Dell that I knew, Dick Gallon an attorney and Peter Workman who was an editor at the time [Note: Workman used to do sales at Dell Publishing]. They had a notion to do a political satire. I had done one of the earlier ones with Jack Sparling, that name may or may not resonate. Jack was an illustrator of comic books as well as other stuff. He and I did a comic, well, it was book, called a flip book. It was political satire and it was the first book that I ever had published and that was in 1964. It was called Instant Candidates 1964. We’d done that and actually Helen Meyer was upset when she learned I had done that. As that was done at Simon and Schuster. She was concerned that I had gone outside the company and said why didn’t you bring it to me? My understanding at the time was that editors went outside the company just because of the presumption of… it would somehow de-legitimize if somebody inside the company had published the book. That’s pretty easy to do. Anyway I had the notion of another political satire based on a superhero. Superheroes had been revived at the time.

Jamie: Especially with the Adam West, Burt Ward Batman show.

DJ Arneson: The sense I have now is that there was a resurgence of interest at the fan level of comics. I got an occasional fanzine. They were mimeographed, done by ardent, earnest, I expect young people who were very enthusiastic about comics. It was my sense was that there was a resurgence of interest in comics in general. They had taken umbrage at The Seduction of the Innocent in where Wertham had challenged the morality of comic books and that they corrupted youth. I know that you’re familiar with that part of comic book history. Tony and I were friends. He was a very reliable artist. I could call Tony with a book that was under pressure and he would be able to produce that quickly, which was essential at the time. When it was due, we only had a prescribed period of time and Tony was always good about being able to produce something quickly. He was also willing to do stuff on spec. That is he would do a cover for a comic book idea or other things. When you are freelance your time is your livelihood and you measure it carefully. Tony did a cover concept for The Great Society comic and I took that to Dick Gallon. He and Peter Workman were in the process of developing a publishing company called Parallax publishing. It later became Workman publishing an enormously successful publishing company. They published the Great Society comic book and subsequently the follow up Bobman and Teddy.

Jamie: Around 1966-7 Dell began publishing some original superhero comics as well.

DJ Arneson: (Laughs) Are you referring to Werewolf, Dracula and Frankenstein? I wrote them.

Jamie: You weren’t publishing under the code so you were able to get away with that.

DJ Arneson: Yeah (laugh). Dell attempted to do some superheroes. You know, it was an attempt. It will be judged by comic book readers and comic book historians. I understand they have been pretty well panned. I’ll take credit or the blame for the writing. Tony illustrated them.

Jamie: Around 1967 there were a bunch of reprints going on, yet new material was being published. How did you decide what to reprint and what new stuff to publish?

DJ Arneson: I don’t know what you are referring to?

Jamie: Some series like Alvin and Combat, the latter issues were reprints of earlier issues.

DJ Arneson: I don’t know anything about that. You mentioned Combat. I thought that was a great series. I’m just reflecting here. Sam Glanzman illustrated Combat. He was really into it, but I’m digressing.

Jamie: So Dell Comic shut down around 72-73?

DJ Arneson: To the best of my knowledge, there was no in-house editor after I left. As I described a little while ago, when I gone to Helen Meyer and put in my resignation and said I was going to be leaving. She offered me this opportunity to remain on staff as editor of Dell comics but come in 3 days a week, and the balance of the week was for me to develop a freelance writing career. For a young, hope to be, freelance writer you couldn’t have a more wonderful opportunity. I did that for the remainder of the year, which I promised her I would do that. After the year was up, I went back and wanted to go full time but she kept me on under the same circumstances. Then it comes down to a specific year, I know I bought a house in Connecticut in ’68 and during that time I was still going in. The final termination as DJ Arneson as Editor, freelance editor, as I was freelancing for Dell was in 1973.

Jamie: Did you do any writing for comic book publishers after that?

DJ Arneson: No, well, wait a minute. I wrote for Charlton. A comic book for Charlton. I wrote for an Undersea guy for.. Tower Comics?

Jamie: Tower comics? Yes. They were in publishing from 65 to 69.

DJ Arneson: Okay yes. I remember they wanted me to do an Undersea guy [Agent]. I did the first issue and I remember I was about to take my family on a long trip to Hamburg or somewhere. I remember I went home and wrote it that evening. That went fast, sometimes it does. I remember there were a lot of undersea stuff, tunnels and rafts and something like that. I remember writing it, but I don’t think I ever saw it. A lot of stuff I never saw. You know, you write the manuscript, you send it in and that’s the end of that.

Jamie: I did see your name attached to a Doctor Graves Magic book when I searched online.

DJ Arneson: I know I did some Romance comics for Charlton. Doctor Graves, that rings a bell but I think that was a, there were comics but it was also..

Jamie: An Activity book?

DJ Arneson: Puzzles and maybe a magic book. There might have been magic tricks in it or something. A lot of this stuff I don’t even have copies of, I wish I did.

Jamie: I noticed certain titles continued on being published at Charlton after they stopped at Dell, like Ponytail. Do you know anything about that?

DJ Arneson: No. Now Ponytail was written and drawn by the creator Lee [Holley], he was a very nice guy when I met him on a couple of occasions when he came to New York. That had originally been a comic strip and Dell did the comic book, I was the editor and he essentially produced the whole thing and sent it to me at Dell Publishing. That was the only comic book that was done outside of the structure that was in place, with synopsis, storyline, storyboards, pencils, inks, colorists, letterers, and so on.

Jamie: When it came to licensing, was it somebody coming to you saying ‘okay we have to do a comic about this property now?’

DJ Arneson: No. As far as the movie studios, they would send the screenplays to me at Dell when there would be movies coming out. And Dell didn’t take that many movies at the time. They were sent to us based on the incredible popularity of Dell as a comic book publisher. From the point of view of a movie production company, a Dell comic client was a bonus. It got the word out about the movie. We would get screenplays by the bundle, well one at a time, but they’d get stacked up on my desk and we had tons of them. We would also get them for television shows that were forthcoming. The decision were often on the screening in the spring for a series that would be released in the fall. I would go with Helen Meyer or in some instances by myself and watch the screening of the Beverly Hillbillies for example. So that was the process, screenplays would come to my desk and I would read them. In most cases they wouldn’t make very good comic books and in some cases it would make sense. I would send them to Helen Meyer and say I believe this would make a good comic book. If she agreed, we would get the license from Warner Brothers of whomever and produce the comic book. It would be based on the screenplay, that is we didn’t create new characters. It would be a comic book of the movie. With a TV series, to use Beverly Hillbillies as an example, we would follow the series in the sense of the characters and the circumstances.

Jamie: Do you know who the distributor of Dell comic were?

DJ Arneson: My recollection was that Western was still distributing. They were printing, I went to the plant at one point. There was still a connection there with Western. But those details I didn’t really have a lot to do with. I was more into producing the comics and once the artwork was out of my hands, that is went to the printer, along with the color specs, that was the last I saw of it. I’m digressing again, but there were tons of storyboards and once they went to the printer and they were done with it, my guess is it was shredded. All of that original art. Some of it terrific and some of it kinda sucked, depending on one’s notion of what is good art, but all of the original comic book storyboards disappeared.

Jamie: That’s too bad.

DJ Arneson: I think so.

Jamie: After you stopped working at Dell I see you did a number of adapted story books for children?

DJ Arneson: I did some original stuff, I did some adaptations.

Jamie: One of them I seen was a Computer Haters Handbook?

DJ Arneson: Yes (laughs), also The Original Preppy Joke book and The Original Preppy Cook book. Those were published by Dell. I was no longer directly connected to Dell, other than I had a lot of friends down there. In the Cook book there are some decent recipes, by the way.