Dave Sim Interview

This interview was originally published in July, 2007. With Dave the first thing many people think about is his controversial views. I read his writing in issue #186 and his Tangents series as well. I must admit, when I first thought about interviewing Dave I had envision getting him in room and going after him like a pissed off Mike Wallace on crack over those views.

This interview was originally published in July, 2007. With Dave the first thing many people think about is his controversial views. I read his writing in issue #186 and his Tangents series as well. I must admit, when I first thought about interviewing Dave I had envision getting him in room and going after him like a pissed off Mike Wallace on crack over those views.

But then I met him and discovered that in person Dave was extremely nice and courteous. He also had a “spider sense” for when somebody was taking a picture of him and he would turn and smile for the camera, even while he was in conversation with others. At TCAF 2005 I saw Dave squinting at a map looking for his table as he had a signing to go to. It was in another area that I had already been to so I offered to walk him over. Later on that convention was the first Doug Wright Awards, I showed up early as did Dave and he struck up a conversation with me. They had examples of Doug’s work on the walls and we looked at them with Dave describing what was great about Doug’s work.

At another convention a female friend of mine wanted to get a sketch from Dave but was a apprehensions about meeting him for obvious reasons. I volunteered to get the sketch on her behalf and she stood line with me until we got close to Dave and then she left. She liked Dave’s work but didn’t want to have a bad experience meeting him. When I got to Dave he asked what I wanted and I said Cerebus and Jaka. He said he would only sketch 1 character and I chose Jaka. Dave did the sketch, looked over to Gerhard who was still working on backgrounds on Dave’s sketches and then did a quick Cerebus sketch too. Both Gerhard and Dave noticed my friend who left the line. Gerhard left his table to have a talk with her and Dave told me later on he almost did this too, but he had a long line of fans wanting sketches.

I don’t think I could go as far as to say Dave and I were friends, but we were friendly to each other. I also didn’t have the heart to go after him regarding his views anymore, even though I disagreed with them. I also had doubts that Dave would allow/agree to that type of interview either as he had his rules. Instead I proposed doing an “introduction” type interview for comic readers who were online, but didn’t read much in the way of comic magazines. I was once one of those type of comic readers. That said, I did learn about his short stay in a psychiatric facility. I had heard other creators reference this but it was good to get the story from him. It was also interesting to get his story about DC’s attempt to buy Cerebus from him, with actual dollar figures and why he turned it down.

I should probably also say that it was once believed that Gene Day died because of how Marvel treated him. I’m friends with one of Gene’s brothers (they live about a half hour from me) and I was told while Marvel’s treatment didn’t help, Gene’s family has a history of heart problems and Gene put his love of work and greasy burgers over his own well being.

After this interview was done, Dave took all the typed questions, attempted to burn them on a CD and then mailed said CD with a sketch on it. Sadly, the burn did not go right, but Dave tried again and got it right the 2nd time. This wasn’t really necessary but Dave wanted to learn how to do it.

—

Dave Sim Interview

Dave Sim is the creator of Cerebus. He began self publishing the comic book in the late 70’s, promised to do 300 issues of the book and did so. It’s a feat few see anybody else repeating. Along the way he selflessly taught people how to self publish their own comic books, helping many to realize their dream of publishing their creations. A few of those self publishers managed to get rich or get better paying work afterwards. With this interview we talk about Dave’s start with comics, Cerebus, the help and difficulties he encountered along the way, what’s he doing now and a lot more.

Note: This interview was done via fax machine. Dave normally only allows interviews to be 5 questions, but let me ask him 20. So an extra thank you goes out to Dave for allowing the extra questions and for being a great interviewee.

Jamie: Assuming you read comics as a boy, which ones did you read regularly?

Dave Sim: I read the Mort Weisinger-edited Superman line of comic books, Superman, Action, World’s Finest, Lois Lane and Jimmy Olsen, later branching out into the rest of the DC line and then Marvel Comics, Warren and then undergrounds by the time I was fifteen or sixteen.

Jamie: I take it you were a big fan of Conan during the 70’s?

Dave Sim: No, I wasn’t really a big fan of Conan in the 70s. I had read all of the Robert E. Howard material once and then-reading the lesser L. Sprague DeCamp knock-offs that came later-swiftly lost interest. I really should go back and find the Howard material at some time and re-read it. I would pick up the occasional issue of Conan if I liked what Barry Smith was doing on it-such as the “Frost Giant’s Daughter” issue that reprinted the black & white strip or the two-part “Red Nails” story as it originally appeared in Savage Tales magazine, but early on-with Dan Adkins and Sal Buscema inking-it just looked like a really bad Marvel comic to me. By that time I was starting to draw on my own, so a comic needed to have something more to it in order to get me excited creatively or make me want to swipe the style of the artist. Barry inking himself definitely had that effect on me. Barry inked by others definitely didn’t have that effect on me and most of his work at Marvel was inked by very incompatible talents.

Jamie: If you didn’t like Conan, why did you create Cerebus to be a parody of it?

Dave Sim: The decision to do Cerebus was based on my insight that what had made Howard the Duck successful was the “funny animal in the world of humans” motif whereas everyone doing work for Quack! (my intended market) was doing all funny animal strips. Since Howard had modern-day sown up that, to me, left the possibility of a science fiction “funny animal in the world of humans” or a sword ‘n’ sorcery “funny animal in the world of humans”. Science fiction required drawing a lot of straight edges and learning how to use French curves properly, so that left only one possibility. Coincidentally I had the unused mascot for Deni’s fanzine and I did a sample page for Mike Friedrich which turned out to be the splash page of issue 1. The fact that it was successful was a very hard lesson in what happens when you do something because you think it’s commercially viable rather than being what you want to do. I was stuck going through the checklist of sword ‘n’ sorcery clichés and was quickly running out of them.

Jamie: Considering Cerebus started off as something you believed would be commercially viable, if you were able to go back and re-do your comic career all over again what would you do differently?

Dave Sim: I’m afraid that one of my core beliefs is to never traffic in the hypothetical which I suspect is one of the reasons that it was possible to finish Cerebus. If you make a choice and then live with the consequences of that choice you are always moving forward. If you make a choice and then spend all of your time trying to assess the different choices you might have made and the possible outcomes of those hypothetical choices, then you just end up spending your life treading water and getting very little done. I conducted my comic-book career the way that I conducted it and it ended up the way that it ended up. I only see what happened, not what might have happened.

Jamie: How did you meet Gene Day?

Dave Sim: I met Gene Day in the summer of 1974. We had started corresponding in the fall of 1973 after John Balge and I had interviewed Augustine Funnel for Comic Art News & Reviews. Gus had started writing for Al Hewetson’s Skywald magazines and told us about his roommate, Gene Day, and that we should talk to him about doing some work for CANAR and that I should ask about doing some work for Gene’s Dark Fantasy. I had already arranged a bus trip up to see my aunt and uncle in Ottawa so I decided to make a side trip to Gananoque on the way and stay over for a couple of days. It ended up being the first of many such trips.

Jamie: I’ve always heard he was your mentor. What exactly did Gene do for you?

Dave Sim: Gene really showed me that success in a creative field is a matter of hard work and productivity and persistence. I had done a handful of strips and illustrations at that point mostly for various fanzines but I wasn’t very productive. I would do a strip or an illustration and send it off to a potential market and then wait to find out if they were going to use it before doing anything else. Or I’d wait for someone to write to me and ask me to draw something. Gene was producing artwork every day and putting it out in the mail and when it came back he’d send it out to someone else. He would draw work for money and then do work on spec if the paying markets dried up. He kept trying at places where he had been rejected. He did strips, cartoons, caricatures, covers, spot illos, anything that he might get paid for. He gave drawing lessons and produced his own fanzines. It was easy to see the difference, to see why he was a success and I was a failure. It was in the fall of 1975 that I bought a calendar and started filling the squares with whatever it was that I had produced that day and worked to put together months-long streaks where I produced work every day. The net result was that I started to get more paying work and a year later I was able to move out of my parents’ house into my own one-room apartment/studio downtown. I doubt that would ever have happened without Gene’s influence.

Jamie: Gene died an early death. Can you tell me about Gene sleeping at Marvel’s office to fulfill a deadline and the health problems that stemmed from that?

Dave Sim: Yes, Gene died at the age of 31 from a heart attack. He had been working for Marvel for several years at that point. He started as an inker which was the thing that he was the fastest at, so he built up a really good reputation as a guy who could turn a late job around in a hurry. He was so fast, the people at Marvel were convinced that he had a whole studio of Gene Day clones working night and day, but it was just him. When I’d go and visit him, he’d have piles of 11×17 photocopies of the jobs he had done-he traded his weekly Cap’n Riverrat cartoon to the local weekly newspaper, The Gananoque Reporter for free photocopying.

When Mike Zeck left Master of Kung Fu to work on Captain America, Marvel was left without a penciller for the title and the editor persuaded Gene to step in which instantly cut his revenue by a substantial amount-he was a much slower penciller than he was an inker. He also ran afoul of then editor-in-chief Jim Shooter’s strict rules about storytelling-that you needed to do the basic six panels to a page method with occasional lapses if you had a good reason for it. Gene, of course was a major fan of Jim Steranko-style storytelling which was exactly what Jim Shooter was opposed to and they locked horns over the subject many times with Gene doing continuous backgrounds in his panel-to-panel continuity (one large background on the page with the action taking place in individual panels set against the one background). Shooter would tell him not to do it and Gene would do it, finally doing I think a five-page sequence that was all one background. At the same time he was doing outside assignments at Marvel including a story for one of the black-and-white magazines (I think it was) which Gene was supposed to pencil and ink.

The deadline got moved up or something and they told Gene on the phone that they were going to have the story “gang inked” over a few days. This was something that Marvel did pretty regularly in the 70s to keep books on schedule. They’d get five or six guys to sit in the bullpen and ink a job to get it done faster. As you would expect, the results were usually horrible. One of P. Craig Russell’s first jobs for Marvel was part of a gang-inking on an issue of Barry’s Conan. For the longest time, my impression of the story was that they had phoned Gene and wanted him to come down and ink the job and that Gene had done so out of loyalty to Marvel even taking the train to Manhattan because he was afraid to fly. It was years later that his brother Dan mentioned to me that what Gene was concerned about was doing as much of the inking himself as he could to keep the job from being a total abomination. The more I think about that, the more it explains what happened. Gene showed up at Marvel and they gave him the address of the hotel he would be staying at. He went there and the place was covered in cockroaches so Gene went back to Marvel and asked to be put up in a better hotel. Nothing fancy, just a place without cockroaches. That was when Tom DeFalco gave him the choice of the roach-infested hotel or sleeping on the couch in Marvel’s reception area. Gene chose the latter, not realizing that they turned the heat off in the building overnight (this was in the dead of winter). So he slept there with his coat pulled over him and developed as a result a kidney infection which stuck with him the rest of his life.

In retrospect, I think the problem Marvel had was that they had no policy for the situation. They had found their solution, they were going to get the job gang-inked. When Gene insisted on coming down to work on it, it just didn’t make sense to them editorially to pay for a hotel room for him given what that was going to add to their costs on the story. For Gene, it was an obvious plus-by coming down and working on the story it would be that much better looking than it would be being inked by whoever happened to be around at the time. But, how the job looked wasn’t as big a priority for Marvel as having the job done. What to Gene looked like a sensible improvement solution looked to Marvel like a needless expense and intrusion by a troublemaker. The same could be said of Gene locking horns with Jim Shooter. To Gene, he was trying to make the book better and more interesting. To Shooter he was making it unreadable and therefore uncommercial.

On Gene’s side of the argument, sales were up on Master of Kung Fu-it had always been a marginal title since Paul Gulacy had left, on the verge of cancellation and now it was turning into a fan favourite again. On Jim Shooter’s side of the argument, good nuts-and-bolts six-panels-to-the-page storytelling always sold better in the long run for Marvel. John Buscema’s Conan outsold Barry Smith’s by a wide margin, as an example. Eventually Shooter fired Gene and I think that, as much as anything, killed Gene Day. His heart and soul were at Marvel Comics. His lifelong dream was to work in the House that Jack Built. Of course, what he failed to see was that working in the House that Jack Built even became an untenable prospect for Jack. And, of course, interviewing as many professionals as I had in my fanzine days, I had a much clearer idea of what Marvel and DC were actually like and just how ruthless the editors could be when the situation seemed to call for ruthlessness (which, as they saw it, it usually did). I knew that in a lot of ways the worst thing you could bring to the table as a freelancer was unwavering company loyalty. For many of the editors at the time, that was just inviting them to rip your heart out. Which, to me, is exactly what Gene did. And exactly what Marvel did.

Dave Sim – 2007 Paradise Comics Toronto Comic Con

Jamie: Prior to Cerebus you did work for other comics. What happened that made you want to self publish instead?

Dave Sim: That was a combination of things. Everyone that I did work for I was either a minor guy on their roster and so didn’t get the attention that I thought I needed or I was a major guy on their roster only because they were too small to get anywhere. They’d announce that the new issue would be out in July and then write you in August saying they hope to get it out by November. There was a sense of time slipping away while I waiting for everyone to get to the project that I was in. Gene was more interested in getting Dark Fantasy out than Hellhound, his proposed comics title. And then he acquired the rights to do an adaptation of Robert E. Howard’s Pigeons from Hell and I knew that was going to push Hellhound even further back. I had printed samples in Quack and Oktoberfest Comics and Phantacea No.1 which I had drawn from someone else’s script, colour covers with black & white interiors and what I figured I needed was a few more samples like that where it was all or mostly my work inside the book. So that was why I decided to do three issues of Cerebus, do it bi-monthly and make sure it came out on time, keep the price the same, keep the format the same, keep the logo the same, have a letters page, keep it to twenty-two pages-basically do all the things right that I thought the other guys were doing wrong and if I fell on my face, well fine, I’d fall on my face and I’d stop complaining about what a lousy job everyone else was doing and just go back to doing it their way. But, at least I’d have three issues of my own comic book to put with Oktoberfest Comics and Phantacea so that editors could see what I was capable of. And as it turned out I was right. To this day, I try to emphasize how important it is to come out on time and everyone just ignores me. They want to know the secret to self-publishing but they don’t want that secret. That secret just sounds like a lot of hard work. Which it is.

Jamie: I understand you worked for Harry Kremer at Now and Again Books, in what years did you do that?

Dave Sim: I worked for Harry beginning December 1st of 1976 when he opened up the downstairs at 103 Queen St. S. which is across the street from where Now & Then Book is now. The hours were 10 am to 9 pm Thursday and Friday and 10 am to 6 pm Saturday and for that I got a grand total of $75 a month. It was all Harry could afford. And I rented my one-room apartment at 379 Queen St. S. for $120 a month which meant that I had to make $45 a month from drawing and writing just to keep a roof over my head. I had about $1,000 in the bank from selling Harry my comic-book collection to help buy some time, but it was definitely sink or swim. As it turns out it was sink, swim or move in with your girlfriend which Deni and I did in April of 1977 so I only had to come up with half of the rent which I think still worked out to about $120 a month.

Jamie: How did Harry help with Cerebus?

Dave Sim: Harry helped in a lot of ways with Cerebus. For starters, he was running the comic-book store that I was living in (it was really my first home, my parents house was just where I slept and stored my comic books) when the direct market started and he was stocking new comic books as well as back issues, new comic books which included ground level titles like Star*Reach which showed me that there was room on the shelves next to Marvel and DC. Then he agreed to publish Oktoberfest Comics in 1976. Through that experience, I found out roughly what it cost to do a black-and-white comic on newsprint with a colour cover and realized that it was a lot more affordable with the new high-speed web offset presses than I had suspected which started me thinking about doing one of my own. And before the first issue was published, he agreed to take 500 copies which, when you consider that our two distributors-Jim Friel of Big Rapids Distribution and Phil Seuling of Sea Gate Distributors-were taking 500 and 1,000 copies respectively tells you what a great vote of confidence and commitment that was from a single comic book store. And then he would also buy artwork from time to time. He bought the complete issue 4 for $220, $10 a page. It may not sound like much, but it definitely paid for a lot of Kraft Dinners which Deni and I pretty much lived on for months at a time. We had our ups and downs over the years-he got seriously offended when I started charging $100 a page U.S. He liked my artwork but he really didn’t think it belonged in that price range. But there’s no question that Cerebus couldn’t have made it through the first few years without his help and, particularly, without the existence of Now & Then Books. Today (6 June 05) would have been his fifty-ninth birthday if he had lived.

Jamie: Is it true that Cerebus was supposed to be titled Cerberus? If so, how did it change?

Dave Sim: What happened was that Deni-before I knew her-had decided to put out a fanzine modeled on Gene Day’s Dark Fantasy. When I met her, in December of 1976, that was what she had come into the store to find out-would Harry be willing to carry copies of her fanzine if she published it? I volunteered to help and wrote down my name which she recognized from the work I had had published in Dark Fantasy. The name she had come up with for her fanzine was Cerebus. So I did a logo for her, the one that was on the first forty-nine issues and told her she really should have a name for her publishing company in the same way that Dark Fantasy was published by Gene Day’s House of Shadows. Her sister came up with Aardvark Press and her brother came up with Vanaheim Press, so I put them together and made it Aardvark-Vanaheim Press. And then I drew a cartoon aardvark with a sword as a mascot. At that point someone realized that the name of the magazine was misspelled. What she had intended to call the magazine was Cerberus, the name of the three-headed dog in Greek mythology who guarded Hades. So I suggested that we just say that Cerebus was the name of the cartoon mascot. The printer in California ran off with the originals and the money for the first issue, so the fanzine never did come out. And that was when I started thinking about my own “funny animal in the world of humans” for Quack! so I decided to draw a sample page of Cerebus the cartoon mascot in my best Barry Windsor-Smith style (see question 6 above).

Jamie: Somebody made counterfeit copies of Cerebus #1. Can you tell us the difference between the two so the online buyers won’t be fooled?

Dave Sim: The easiest way to distinguish the real Cerebus No.1 from the counterfeit is that the inside covers are glossy black on the counterfeit and a flat black on the real ones. The next easiest way is that if you look at the areas of solid black on pages 9, 10 and 11, they look “dusty”. That’s because the counterfeit was shot from a printed copy where there was already a slightly speckled quality because it was printed on cheap newsprint, so when that slightly speckled quality was photographed, the-now doubled-slightly speckled quality ended up looking like a fine layer of dust over the entire page because there is so much solid black on those three pages.

Jamie: Did you ever discover who made the counterfeits?

Dave Sim: I have my suspicions as to who did the counterfeit but, no, the FBI never managed to catch the guys who were selling them-the “mules” folded their operation as soon as word started to spread-and therefore there was no route to anyone who was behind the scam. I certainly wasn’t about to accuse anyone publicly without evidence to support it but, yes, I’m pretty sure I knew who did it.

Jamie: I hear that after issue #11 you over-worked yourself into a nervous breakdown. What were you doing at the time?

Dave Sim: Twenty-six years later on, I think it would be more accurate to say that I had achieved a false level of transcendence that I had been looking to achieve through LSD-the psychic equivalent of a massive and pleasurable electric shock-that left me incapable of reassuring my wife (within her own very limited frames of reference) that I was okay: with the result that she freaked out at one point and called my mother and she and my mother locked me up in a psych ward at the local hospital for a couple of days.

Jamie: How did you recover from a nervous breakdown and continue on?

Dave Sim: There really wasn’t anything to “recover” from. I had gone through the false transcendent state and come out the other side. The only thing I really needed to recover from was the massive doses of depressants they had given me in the psych ward. That took two or three days during which all of my muscles and motor functions were seriously malfunctioning-it felt as if I had pulled every muscle in my body so that just speaking and walking required Herculean forces of will in order to achieve. Essentially, at that point-never again wanting to experience that severe crippling effect-I began to live two different lives simultaneously. I learned how to portray myself as a normal person in order to keep my wife and parents from locking me up in any more psych wards while at the same time I began to explore all of the thoughts and experiences that I had had over the period of the false transcendent state and began to work towards putting them all down on paper in the Cerebus storyline. When I realized, a month or two later, how large and difficult a task that was going to be, I decided to make Cerebus into a 300-issue project in order to encompass it all and leave room for my own best assessment of the aftermath. The documentation of the state itself went from about issue 20 to about issue 186. I was able to stop leading my double life once I was divorced in 1983 and I no longer had the on-going threat hanging over my head that my freedom depended on my wife and mother believing me to be sane.

Jamie: How did you meet Gerhard?

Dave Sim: I had heard a great deal about Gerhard because he was the “golden boy” of his high school clique, one of whose members was Deni’s high-school aged sister, Karen. He was the chief set designer and star of a high-school production “You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown” and also an illustrator and the high-school clique was his major support group. They collectively believed in him and his prodigious abilities to the same extent to which he didn’t believe in himself: which is to say thoroughly and completely. At one point the high-school clique was having a Halloween party and Karen, Deni’s sister, and Bob her boyfriend and later husband came by the apartment to smoke a joint with Gerhard and his (then) girlfriend Laurel. So far as we know that was how I met Gerhard. It would’ve been Halloween of 1981 or 1982.

Jamie: I’m surprised more artists don’t try and pair up with somebody to help out with backgrounds. Why do you think you and Gerhard have worked so well together for the past 20 years?

Dave Sim: I’m surprised, as well, that more artists don’t pair up with background artists. The history of the comic-book field is filled with things that worked really well that no one else ever attempted. Look at Will Eisner’s The Spirit-what a great idea to do a comic-book supplement for newspapers and yet no one ever tried it again. It’s certainly something that I would recommend. I suspect fine arts courses and architectural schools are filled with guys who just have a love of drawing still-life’s, which is all that backgrounds are. Of course Gerhard grew to hate pen-and-ink drawing which had been one of his abiding passions when he had to do the volume of drawing required, so you won’t be seeing him recommending it as a career choice anytime soon. But, yes, I do think that guys who love writing and lettering and drawing people should look around for guys who like to draw inanimate objects. Mutual tolerance would, I think, best describe how the collaboration worked and how it continues to work. If I really needed something to go in the background, I’d be specific with Gerhard but if not, I let him do whatever he thought would look best. I always got my own best results by doing what I thought was best and always got second-rate results when someone was telling me what to do, so it just seemed natural to me to treat Gerhard the same way. If you want the best results let the guy call his own shots.

Jamie: I recently read that DC made an offer to buy Cerebus from you at one point. When did that happen and how much did they offer?

Dave Sim: Those negotiations took place over the course of 1985 to 1988, I think it was. Ultimately they offered $100,000 and 10% of all licensing and merchandising and that I would be allowed to keep doing the monthly black-and-white and Swords of Cerebus on my own. In the middle of the negotiations I came up with the idea of the High Society trade paperback and selling it direct to the readers which brought in $150,000 in the space of a few weeks and made their offer look kind of puny by comparison. What I wanted to develop was a Superman contract-a contract that would have been fair to Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster-where DC could pick the revenue thresholds, but at some point we would split all revenues 50-50 just as is done with syndicated comic strips. No go. They made a final offer to give me the whole $100,000 all at once or half now and half later on which, to me, completely missed the point. You start with a dollar amount and negotiate upward, you don’t say “You can put it all in your right front pocket or you can put half in your right front pocket and half in your back pocket.” When I realized that Paul Levitz wasn’t going to budge, I packed it in.

Jamie: Now that Cerebus is done are you more open to selling it?

Dave Sim: No, not really. The difficult part is done now-actually writing and drawing the 6,000 pages so it’s more like it’s nice that the book still keeps us busy, me with answering the mail and Ger doing the business side and renovating the house and both of us working on Following Cerebus and developing a website for selling the artwork and putting together a First Half package of the first six volumes in a boxed set for Christmas, 2006. If we sold it we’d just have a pile of money and nothing to do. I really like being one of the two Cerebus custodians. Part of the fun of sculpting a statue over twenty-six years is spending the rest of your life washing the pigeon droppings off of it every day.

[Note: Following Cerebus is a magazine that Dave and Gerhard work on. You can find more info about it here: http://spectrummagazines.bizland.com/]

Jamie: I understand that since Cerebus ended, you are now organizing your archives and this will likely take another few years. What do you plan to do with your archives when you are done?

Dave Sim: Actually I have a lot of help from the Cerebus Newsgroup readers at Yahoo.com who are working out all the computer technicalities and Margaret Liss of the www.cerebusfangirl.com website who has started scanning in all of my notebooks. After that it will be all of my comics material starting with my first fanzine in 1970 through until the present day, all of the paperwork and correspondence, interviews, reviews, etc. in chronological order. As she scans that, she’ll be “key-wording” each document so that it can be indexed for content and you’ll be able to type in, say, “Kevin Eastman” and it will call up every document that mentions him. The idea is to arrive at a point where that becomes the primary research resource for Cerebus. Someone wanting to do an interview like this, I can just go through and check off the questions that they can find answers to in the Cerebus Archive so that I don’t have to keep answering the same questions over and over and over. Basically the same thing that I did with the Guide to Self-Publishing where I went out and promoted self-publishing through the Spirits of Independence stops for a couple of years and then wrote down everything I had been telling people and now I can just give them a copy of the Guide to Self-Publishing if they come to me for advice. I almost never get asked about self-publishing anymore for that reason.

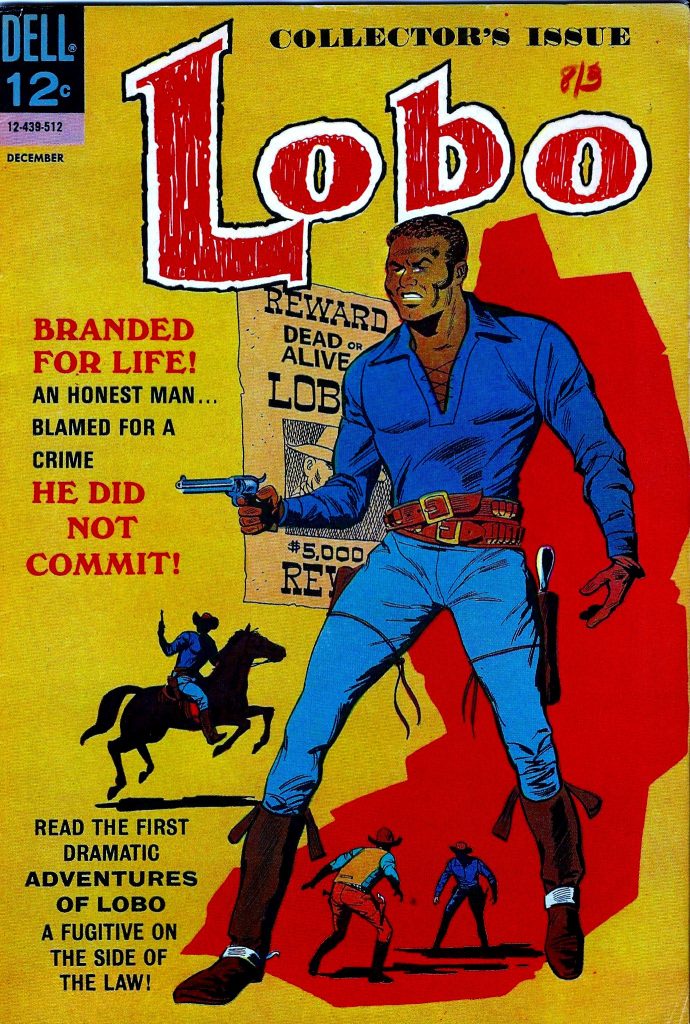

During my research into comic book history I learned about Lobo, the first black comic book character with their own solo title. This was published in 1965, long before Marvel’s Black Panther. There was little to no information about Lobo’s creators. It was known that Tony Tallarico drew the comic book.

During my research into comic book history I learned about Lobo, the first black comic book character with their own solo title. This was published in 1965, long before Marvel’s Black Panther. There was little to no information about Lobo’s creators. It was known that Tony Tallarico drew the comic book.